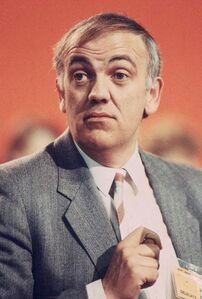

David Penhaligon

| David Penhaligon | |

|---|---|

| Name | David Charles Penhaligon (6 June, 1944- 22 December, 1986) |

| Nicknames | The Voice of Cornwall (the media) |

| Politics | |

| Party | Liberal |

| Constituency | Truro (October 1974 - 22 December, 1986) |

| Positions | • Liberal Party President (1985 - September, 1986) • Treasury Spokesman (July 17, 1985 - 22 December, 1986) • Head of the By-election Unit (1983 - 1985) |

| Likes | Cornwall, mining, nuclear deterrents, the minimum wage, political alliances |

| Dislikes | CND |

| Friends | David Steel, John Pardoe, the SDP |

| Enemies | Impressively, no one |

| Relationships | |

| Partners | Annette Penhaligon (1964 - 1986) |

| Children | Matthew (1972), Anna (1977) |

| Personal Attributes | |

| Nationality | Cornish |

| Religion | Church of England |

| Sexuality | Straight |

| Height | ? |

| Eye Colour | ? |

| Handedness | ? |

| Accent | Cornish |

| Languages | ? |

A reforming radical often performing as a Cornish comic.~ Unknown

[He had] a closer grasp of national electoral politics ... than any other Liberal MP.~ Hugo Young

David Penhaligon was a Cornish MP best known for his jovial personality and his tragic, untimely death. The strength of the Liberal Democrats in southern England is his lasting legacy, but he was also notable during his lifetime for being one of the few Liberal MPs with a shred of common sense. He played a key role in stabilizing the Lib-Lab Pact and the Liberal-SDP Alliance and in bringing Liberal policy back into line with the sensibilities of the electorate, and the fact that David Steel survived his tenure as Liberal leader without suffering a nervous breakdown can probably be attributed in large part to Penhaligon's influence.

Life and Career[edit | edit source]

Early Life and Engineering Career[edit | edit source]

David was born on D-Day, a fact he would use to rhetorical advantage in later life, and only narrowly escaped being named "Montgomery". Charles and Sadie Penhaligon had three children, of whom David was the second. Charles ran a garage and the Kenwyn Hill Caravan Park in Truro, where David grew up surrounded by the poor and transient, rather than the children of other middle class businessmen on the far side of town. It was the beginning of his political education.

David attended the local independent Truro School. He was a sickly child and missed whole terms due to illness, but his innate curiosity kept him learning. He had developed a knack for fixing mechanical devices by hanging around his father's garage and figuring out how things fit together, and at sixteen he left school to become a fitter and turner apprentice at Holmon Brothers, a drill manufacturing firm in nearby Camborne. The company saw his potential and sent him back to school to study mechanical engineering at Cornwall Technical College. David qualified as a Chartered Mechanical Engineer in 1973 and eventually became head of Holmon's research division. He took a second job as a sub-postmaster in Chacewater in 1967, although he left the actual work of running the sub-postoffice to his wife Annette.

Early Political Career[edit | edit source]

I only got elected because I was too naive to realise it was impossible.~ David Penhaligon

David decided to join the Liberals in 1963, after his testimony as an important witness in a murder case involving a man from the family caravan site failed to prevent the conviction and execution of the defendant. Appalled by what he saw as a miscarriage of justice, David joined the Liberals to campaign for the abolition of capital punishment. (In true Lib Dem spirit, he would later vote in favor of it in the Commons.) He became the leader of the Truro Young Liberals and built up the feeble local party into one of the strongest in Cornwall, but despite these accomplishments the Liberals refused to select him as a parliamentary candidate in the 1968 election because they felt his strong Cornish accent would be off-putting to the voters. In 1970 he stood in Totnes but came a distant third, just like every other Liberal candidate in the constituency since 1945.

In 1971 he was selected as the candidate for Truro, an equally bad bet, but this time David was fighting on his home turf, he was an experienced campaigner and he had three years to nurse the constituency before the election. In February of 1974 he more than doubled the Liberal vote share, cutting the majority of the incumbent Tory MP to 2,561. In the second election that October he won the seat by 464 votes.

On the Backbenches[edit | edit source]

MPs are divided into three categories: 1) workoholics, 2) hard workers, and 3) if you can discover anything they do, let me know.~ David Penhaligon

David's parliamentary career got off to an endearingly earnest start when he turned up to the Commons at 9:00 AM, little realizing that his colleagues kept a schedule more reminiscent of university students than working adults and he was five hours early. He'd rung the Whips' Office to ask the date of the first sitting of the new Parliament but hadn't thought to ask the time. David learned to be more careful with his research, but he retained his early enthusiasm and quickly developed a reputation as a vigorous campaigner for local issues. He was a strong advocate for the Cornish mining and fishing industry, once telling the House that "you need more in an economy than just tourism, ice cream and deckchairs". He was also notable for his sense of humor and friendly manner- both allies and opponents enjoyed his jovial speeches, and he was almost universally liked by his colleagues and his constituents.

The Lib-Lab Pact[edit | edit source]

David entered Parliament at a turbulent time for the Liberal Party. They had more than doubled their parliamentary seats during the 1974 elections, but in 1976 the party leader Jeremy Thorpe was caught up in a sex scandal that would culminate with him being put on trial for conspiracy to murder. In May he resigned as leader, but it was too late; the Liberal Party was tainted by association. Inexperienced and reluctant to condemn their colleague, the party leadership were unable to contain the story. Worse still, Thorpe's resignation was followed by what was for the Liberals an unusually nasty leadership election. David supported his fellow Cornishman John Pardoe, but in the end David Steel won handily by exploiting Pardoe's quick temper and gained control of an unhappy, divided party. Steel immediately appointed a shadow frontbench team- the entire party, since there were only thirteen of them- and David Penhaligon was given the transport and industry portfolios.

All was not well within the Labour Government, either. Their majority had been eroded by successive by-elections until in March of 1977 Prime Minister Jim Callaghan found himself facing a no confidence motion. He approached Steel and asked for his support, and found the Liberal leader eager to reach an agreement. For Steel a Lib-Lab Pact was an end in itself, but the rest of the party felt that they had Callaghan backed into a corner and they should take advantage of the opportunity to extract some policy concessions. They were especially concerned about securing a proportional representation system for the upcoming European Parliament elections, which the Government supported in theory but refused to legislate on. David Penhaligon felt that they would never be able to justify propping up the failing Labour government to the voters or to their own activists if they could not at least get this one basic concession.

Unfortunately for the Liberals, they sent Steel to broker the deal. A poor negotiator in the best of circumstances, he was especially biddable this time, since he thought the pact itself was more important to the future of the Liberal Party than any specific policy objective. He came back with an agreement that contained not a single policy commitment, not even the all-important assurances on PR. David felt that he could not sign on to the pact under those terms, and former leader Jo Grimond did not want it at all.

The two rebels were trapped between a rock and a hard place. To prove that the Liberals were responsible enough to govern, they had to demonstrate they were capable of collective responsibility and either publicly support the majority decision in favor of the pact or resign their frontbench positions. If they resigned there would be no one to replace them, and it would make the party look weak and divided and damage Steel's credibility. They decided to go along with the majority, and David eventually came around to the idea of the pact. At the Liberal Conference in September he defended it against a motion calling for its dissolution, saying that although the Liberals had been far too modest in making demands of Labour and they must be prepared to walk out if they couldn't get enough policy concessions, it had achieved an economic revolution in Britain.

In January 1978, the Liberals called a special assembly to decide whether or not to continue the pact, and David distinguished himself as one of its most persuasive advocates. Although the Liberals had minimal success in getting their own policies through, the Government's shaky position and internal divisions with the Labour Party meant they were quite effective at blocking the Government's. David single-handedly stopped Tony Benn from nationalising the electricity industry, and the other Liberals could boast similar victories in their own portfolios. Obstructionism and the improving economy were enough to convince the Liberals to continue the pact for another eight months.

David was also concerned about what would happen to the Liberals when the Government collapsed and an election was called- as he would put it later, "Turkeys don't volunteer for Christmas!" The Government was unpopular, the Liberals condemned for propping it up, and the Thorpe affair continued to simmer in the background. Thorpe insisted on standing in the next general election and the leadership were unwilling to chuck him out. David worried about how the scandal would affect his prospects in his own nearby constituency and refused to campaign for Thorpe, even going so far as to openly brief against him in the papers, but in the end it didn't matter- in the 1979 election Thorpe lost his seat and David dramatically increased his own majority.

The Alliance[edit | edit source]

I despair of these people. You cannot teach them that their own fancy ideas count nothing with real people.~ David Penhaligon, on the Liberal Conference's vote for unilateral nuclear disarmament

| Full List of Appointments |

|---|

| • Spokesman for Transport, Industry and Energy (? - 1983 - ?) |

| • Head of the By-election Unit (1983 - 1985) |

| • Treasury Spokesman (July 17, 1985 - 22 December, 1986) |

| • Liberal Party President (1985 - September, 1986) |

Personal Life[edit | edit source]

In 1968 David married his wife Annette, who would prove a crucial support in his political career. A local girl from Tregony, she was a devoted to Cornwall and the Liberal Party as her husband was, and she was instrumental to his political success. Throughout his time in Parliament she would be David's PA.

Ideology[edit | edit source]

I worked in a big factory employing about a thousand people and my socialist friends told me it should be nationalised. I said if it was run by London it wouldn’t make fourpence... and I took the view that there was nothing wrong with my company making a profit, that giving some of it to David Penhaligon wouldn’t put right.~ David Penhaligon

Portrayal[edit | edit source]

In the Media[edit | edit source]

Reporters liked David as much as everyone else did, and as result he got very positive press coverage. He appeared frequently on the radio or Question Time, where his engaging personality elevated him to national prominence despite his focus on local issues.